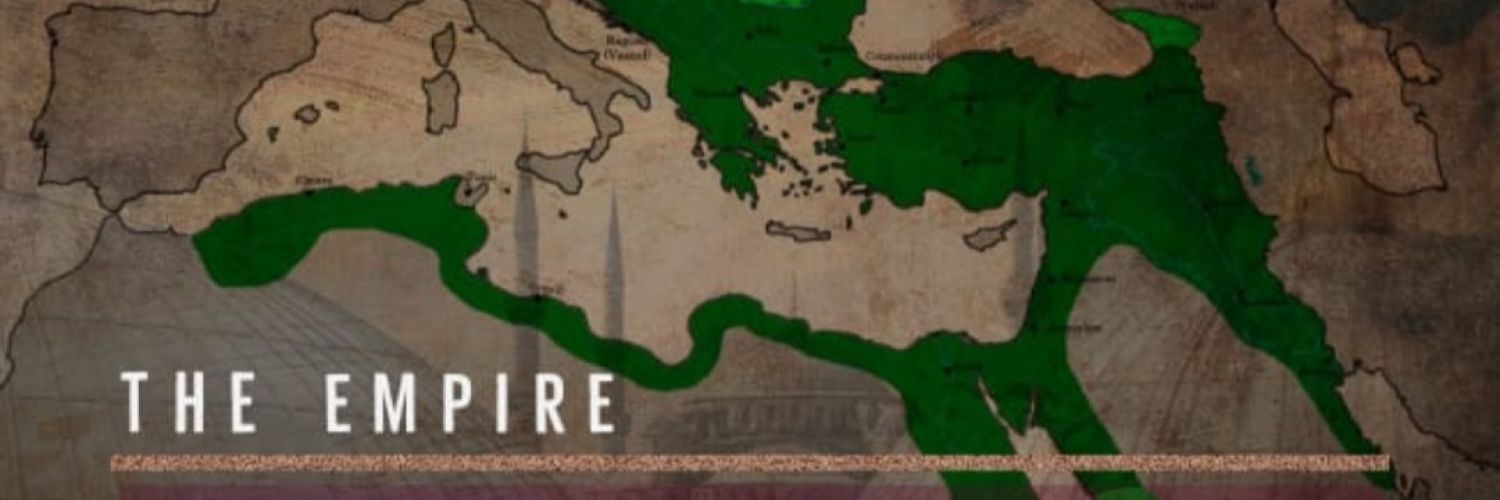

[19] The Ascent and Decline of The Ottoman Empire

In The Name of Allah, The Most Merciful, The Bestower of Mercy.

Sultan Murad III

He rose to the throne after the passing of his father and demonstrated a strong passion for the sciences, literature, and poetry. He was fluent in three languages: Turkish, Arabic, and Persian, and exhibited a preference for Sufism. He provided support to scholars and generously allocated significant funds to soldiers, totaling 110,000 gold lira, which effectively mitigated the unrest that often stemmed from delays in the distribution of these payments. One of his first measures was to enact a decree banning alcohol, which had become prevalent among the people, especially the Janissaries. This decision incited a rebellion among the Janissaries, compelling him to retract his prohibition. This episode underscores the signs of the state’s deterioration, as the sultan struggled to impose the alcohol ban and maintain religious laws. It also reflects a departure of the Janissaries from their foundational Islamic principles of noble upbringing, commitment to Jihad, and aspiration for martyrdom.

He upheld the policies set forth by his father, participating in numerous military campaigns across different regions throughout his reign. In 1574, after King Henry of Poland fled to France, the Ottoman caliph recommended that the Polish leaders elect the Prince of Transylvania as their monarch, a suggestion they accepted, thereby placing Poland under Ottoman protection by 1575. This arrangement was recognized by Austria in a peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire in 1576, which remained in effect for eight years. In 1576, following an incursion by the Tatars into Polish territory, the Polish sought aid from the Ottoman Sultan, who then formally declared their protection through an official treaty. He reinstated privileges with France and Venice, thereby augmenting specific consular and commercial rights in their favor. Significantly, the French ambassador was accorded precedence over all other ambassadors during official ceremonies and governmental gatherings. The surge of ambassadors arriving at the Sublime Porte in pursuit of trade agreements subsequently provided a rationale for genuine intervention in state matters. During the reign of Sultan Murad, Isabella, the Queen of England, obtained exclusive privileges for her merchants, permitting British vessels to display the British flag and gain entry to Ottoman shores and ports.

In the year 985 AH (1577 AD), following the upheaval in Persia after the passing of Tahmasp, the Ottomans initiated a military campaign that effectively covered extensive regions in the Caucasus, resulting in the capture of the city of Tbilisi and Kargestan (Georgia). Later, in 993 AH (1585), the Ottomans advanced into Tabriz, where the sultan’s forces secured dominance over Azerbaijan, Kargestan (Georgia), Shirvan, and Luristan. Upon the ascension of Shah Abbas the Great to the Persian throne, he endeavored to establish a peaceful resolution with the Ottomans, consenting to cede the territories that had fallen under their control. Additionally, he vowed to refrain from disparaging the rightly guided caliphs Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman, may Allah be pleased with them, within his domain, and dispatched a cousin named Haidar Mirza to Istanbul to ensure the adherence to their agreement.

The Janissaries instigated a revolt in the Ottoman provinces after the conclusion of hostilities. The Sultan had dispatched them to engage in combat in Hungary, but they faced defeat at the hands of Austria, which was allied with Hungary. This defeat resulted in the occupation of numerous strongholds, although these were subsequently recaptured by Sinan Pasha. Furthermore, the princes of Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania declared their insurrection and formed an alliance with Austria against the Ottomans. In retaliation, Sinan Pasha launched an offensive against them in 1003 AH / 1594 AD; however, he was unable to secure a victory and lost several cities in the process.

Consequently, the assassination of the Grand Vizier, which stemmed from the machinations within the Sultan’s court, was further exacerbated by foreign agents opposed to the influence of such a capable minister. He was committed to principles of integrity, wisdom, statecraft, effective leadership, meticulous planning, and administrative oversight, while also keeping a close watch on provincial governors and capitalizing on opportunities. His untimely death represented a significant setback and a profound challenge, paving the way for malevolence in the processes of appointing and dismissing grand viziers. This situation fostered a competitive struggle for power that ultimately undermined the sultanate. The ensuing chaos led to instability within the nation, provoking mutinies among certain military factions that the government found difficult to quell. As a result, these internal conflicts and uprisings contributed to Poland’s withdrawal from the Ottoman Empire and its subsequent engagement in hostilities against it.

A faction within the Jewish community perceived that the moment had finally come to fulfill a long-cherished aspiration, leading them to migrate in successive waves to Sinai for settlement. Their initial approach was centered on establishing a foothold in the city of Tor, a strategic decision owing to its favorable position on the eastern coast of the Gulf of Suez, which boasted a port conducive to commercial shipping. This port accommodated vessels from Jeddah, Yanbu, Suakin, Aqaba, and Qulsum, while the city was also linked by land routes to Cairo and Farama. As a result, this arrangement enhanced external communications for the Jewish settlers, safeguarding them from isolation and enabling ships to dock at the port of Tor, thereby facilitating the arrival of new groups of immigrants.

A Jewish individual named Abraham spearheaded a migration initiative, relocating to Al-Tur with his family. Upon their arrival, the Jewish community in Al-Tur created disturbances for the monks residing at St. Catherine’s Monastery. This situation led the monks to submit formal complaints to the Ottoman sultans and their governors, detailing the grievances related to the disruptions caused by these specific Jews. They reminded the authorities of the Ottoman obligation to safeguard their community and cautioned against the settlement of these Jews in Sinai, particularly in Al-Tur, as it could lead to potential unrest. In accordance with Sharia, which mandates the protection of non-Muslims, Ottoman officials were prompted to issue three decrees during the reign of Sultan Murad III. These edicts ordered the expulsion of Abraham, his wife, children, and all other Jews from Sinai, forbidding their future return to the region, including the city of Tor. [Footnote a] Sultan Murad III passed away on January 16, 1595, at the age of 49 and was interred in the courtyard of Hagia Sophia. [1]

————————————-

Footnote a: It is crucial to recognize that the author did not provide an in-depth account of the disturbances, and every situation has multiple perspectives. This necessitates a careful approach when considering blame directed at particular Jews or any individuals involved, whether they are Jewish or non-Jewish, unless clear evidence is presented to clarify the underlying issues. Furthermore, we should not automatically assume that the monks were entirely blameless, as the author did not specify the reasons behind their accusations against certain Jews. Given the historical tensions that may have existed between some Jewish and Christian communities due to religious differences, we must exercise even greater caution in our judgments regarding this particular incident. We are commanded to do justice when passing judgement, as Allah stated:

فلذلك فادع واستقم كما أمرت ولا تتبع أهواءهم وقل آمنت بما أنزل الله من كتاب وأمرت لأعدل بينكم الله ربنا وربكم لنا أعمالنا ولكم أعمالكم لا حجة بيننا وبينكم الله يجمع بيننا وإليه المصير

So unto this (religion of Islam, alone and this Qur’an) then invite (people) (O Muhammad ), and Istaqim [(i.e. stand firm and straight on Islamic Monotheism by performing all that is ordained by Allah (good deeds, etc.), and by abstaining from all that is forbidden by Allah (sins and evil deeds, etc.)], as you are commanded, and follow not their desires but say: “I believe in whatsoever Allah has sent down of the Book [all the holy Books, this Qur’an and the Books of the old from the Taurat (Torah), or the Injeel (Gospel) or the Pages of Ibrahim (Abraham)] and I am commanded to do justice among you, Allah is our Lord and your Lord. For us our deeds and for you your deeds. There is no dispute between us and you. Allah will assemble us (all), and to Him is the final return. [Surah Ash-Shuraa. Aayah 15]

[وَأُمِرۡتُ لِأَعۡدِلَ بَيۡنَكُمُۖ – and I am commanded to do justice among you]- Meaning, when passing judgement regarding that which you have differed between yourselves; therefore, your enmity and hatred does not prevent me from judging with justice between you. And part of justice is that when judging between people who make different statements – amongst the people of the Scripture and others – one accepts what they possess of truth and reject what they possess of falsehood. [2] [End of quote]

Indeed, we are not in a position to judge precisely what really happened between those monks and Jews because the author did not provide full details. The knowledge of all affairs is with Allah.

[1] Ad-Dawlah al-Uthaniyyah Awamil An-Nuhud Wa Asbab As-Suqut 6/323-326

[2] An Excerpt from Tafsir As-Sadi

Donate

Related Posts

Recent Posts

- A Dialogue with Eric R. Mandel on Entitlement, Fair Play, and Accountability

- Verse 24 Surah As-Sajdah

- Liars in the Time of Tribulation: Those Who Appeared, Those Who Remain, and Those Yet to Come

- Interpreting Current Events with Respect to the Signs of the Hour is the Task of Living Salafi Scholars – Not Social Media Influencers

- Verses 267-268 Surah Al-Baqarah